What’s your favourite dinosaur?

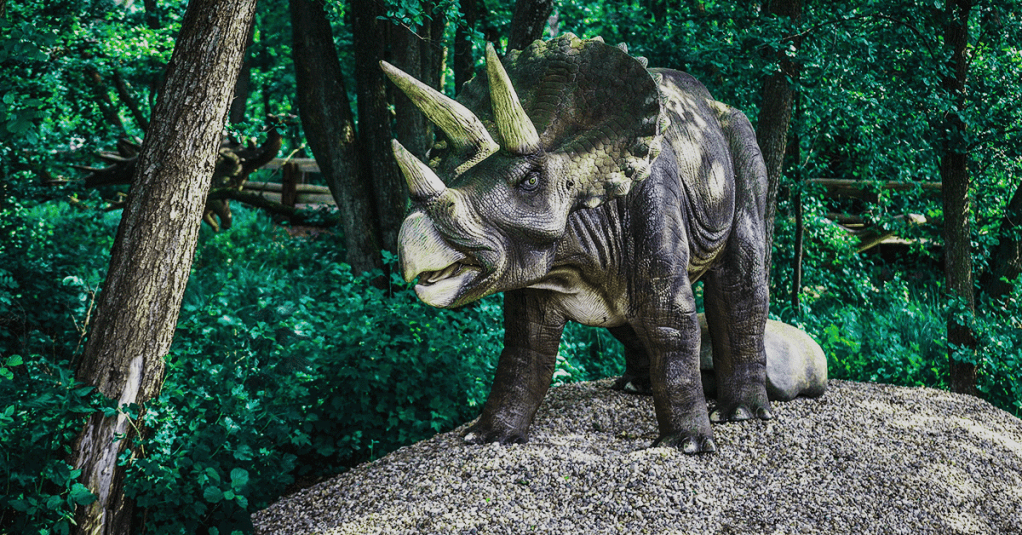

I’m not sure how I could trust an adult who claims not to have a favourite dinosaur. I remember, as a six year old, going to Wookey Hole (I have been spelling it Wookie my whole, Star Wars-loving life) and asking for a toy triceratops (three horns, ruffled collar, your typical renaissance dandy dinosaur) in the gift shop. The shop assistant had no idea what I was talking about and I had to point one out on a poster. I remember my Dad being impressed that I was explaining the different types of dinosaurs to someone who worked in actual dinosaur country.

Triceratops was my favourite, but I always had a soft spot for stegosaurus, which for a long time was thought to have two brains. Until that misconception was corrected I imagine that baby stegosauruses had a hard time of it in dinosaur kindergarten, being picked on for being the class swot, which was an experience I could readily relate to. I was regularly picked on for such heinous crimes as knowing big words, not speaking with a Derbyshire accent, and of course for being gay; all before hitting double figures in terms of age.

Primary school was a confusing period, sexually speaking. I imagine the confusion stemmed from not knowing what sex even was and yet hearing about it from my peers regularly. Did you play ‘Tiggy’ at school? We had multiple versions of the regular ‘tig-you’re-it’ game:

- ‘Tiggy off ground’: you can’t be tigged if your feet aren’t touching the floor. We used to play it on the walk to school too, with cars – you had to be off-ground when a car went past. There was a church next to our primary school and once I was clinging on to a high wall with the last layer of cells on the tips of my fingernails when an entire funeral procession drove past at 5cm per hour.

- ‘No tiggy butcher’: no idea why they are called your butcher, but you can’t tig the person who tigged you.

And the most confusing version:

- ‘Tiggy bummer’: a regular tig, but when you’re tigged you have to stand stock still, arms out wide, feet slightly more than shoulder width apart, like a scarecrow speaking at a Conservative party conference. You have to stand like that until one of the other players runs up behind you and pelvic-thrusts you in the buttocks, at which point you have been ‘bummed’ and you are free to run about again.

Riddle me this: how is it that I was bullied for being gay; and that ‘gay’ was, in 1977, the worst schoolyard slur that existed, worse than ‘snitch’, worse even than supporting dirty Leeds; but tiggy bummer is a perfectly acceptable playground game for a bunch of heterosexual six year old Alphas? I cannot get my head around this phenomenon, which I wrote more about here [trigger warning for poetry]: ‘Growing up ‘gay’ (with the ‘gay’ in air quotes)’.

Old Whittington, the small suburb of Chesterfield where I lived as a kid, is so old that it’s mentioned in the Domesday Book. In fact, many of the books in Old Whittington Library where I grew up were first editions from the same time as the Domesday Book. Across the road from the library is The Revolution House, where in 1688 three men met up to begin the sequence of events that would become The Glorious Revolution and see William of Orange ascend to the throne. This is what happens when there’s nothing to do in the pub, you get talking and before you know it, you’ve started a revolution. The following year dominoes and darts were both invented and there hasn’t been a revolution in the UK since.

The dinosaur books were in the far corner of the single-room library, between the window and the librarian’s table, two shelves up from the bottom. One day, perusing the shelf for a primary source on dinosaurs that I hadn’t read a dozen times, was a slim pink volume. Finally, something new to read! The book was called, ‘Have you started yet?’ and while the cover wasn’t immediately dinosaur-related it was on the dinosaur shelf (which I had been stealthily reordering with each visit so that the books ran chronologically, which made more sense than a simple Dewey system; I think I was reordering the late Permian period this particular day) so what else could it be?

I began to flick through. It seemed surprisingly light on dinosaur content. There were some diagrams I didn’t understand, but ‘period’ appeared a lot, and the whole history of dinosaurs is broken into periods so that at least was comfortingly familiar. But as I read I couldn’t shake the feeling that somehow I wasn’t supposed to be reading it, so I put it back on one of the other, boring, non-dinosaur shelves that took up a depressing amount of room in a library that itself must have been around since the Capitanian mass extinction event.

Of course now I know that the book must have been ‘Have you started yet? You and your period: getting the facts straight’, written by Ruth Thompson and first published in 1975. The five furtive minutes spent flicking through that, and one afternoon in Mr Yates’ class, was my whole exposure to sex and reproduction education until my mid-teens (well, human sex and reproduction; I could probably have written ‘Have you started yet for dinosaurs’ even at age six).

By the time I had another lesson I’d already lost my virginity, to a girl no less, despite almost a full decade by now of being bullied for being gay, and being the person least likely to have any form of intimate contact in the whole school. There were lathes in Mr Clay’s woodworking class who got more action than me (here I was going to throw in a crass joke about the lathes having their knobs fondled regularly but I decided against it on the grounds of taste, but also because I don’t know if the knob on a lathe is called a knob and I’ll probably get called gay for not knowing that manly information) and I still believe that if I hadn’t met this person at this time, I’d probably still be a virgin now. Once, some time soon after my first time, I spotted a white string between her legs. I honestly thought it was a bit of cotton from the bedsheets and went to pick it off, earning myself a swift and urgent rebuke.

Losing my virginity was my third sex ed lesson, and that encounter was my fourth. My fifth, strictly speaking, wasn’t mine.

One day at school – I don’t know about now but in the mid-80s boys and girls did their physical exercise lessons separately and other genders, like recycling and flat back threes with wing-backs, apparently did not exist in the UK at this time – the boys came out for their PE lessons and the girls never appeared. We’d normally see them, they’d be in the gym doing dance or gymnastics whilst we did football or cross-country outside, but on this one day they stayed locked in their changing rooms.

At break we asked them where they’d been. They’d been told not to talk to the boys about it. Later, because some of the girls knew that it was okay to talk about, we learned that they’d been given a talk about periods and sanitary products, but yes, had been told strictly not to talk to the boys about it. We weren’t supposed to know and definitely weren’t supposed to discuss it. Why this duty fell to the games mistress, as we called that post, I cannot guess.

After that (I did not take biology as one of my CSEs or O-Levels) I can recall one further science class in which we covered human reproduction. Again, disappointingly, nothing about dinosaur reproduction, which seemed to me to be one of many glaring lapses in the national curriculum at this time. This one lesson, and you’ll note that this was a science lesson where sex was discussed in scientific terms rather than in sociological terms as a part of the human experience and something that most of us would go through, was my sixth and final sex ed lesson. I was four months short of my seventeenth birthday when I left school, and I could tell you more about the mating rituals of didelphodon in present day North America than teenagers in present day North of England.

It is Aristotle who is credited with the aphorism, “Give me the boy until the age of seven and I will give you the man”. We know more about child development now than A-stots (although you’d never know it from looking at the budget for Sure Start in the UK) but I think his general point holds water. There are so many resources for helping children and young people understand – not just procreation and reproduction, but sex and masturbation, relationships and consent – which were completely absent from the conversation until so recently. Did you know that even in the sixties, Roy Levins’ popular textbook ‘Essential Medical Physiology’ had no index entries for penis, vagina, coitus, erection or ejaculation? “Physiology courses skipped orgasm and arousal, as though sex were a secret shame and not an everyday biological event”, writes Mary Roach in ‘Bonk: The Curious Coupling of Sex and Science’, an informative and frequently hilarious book that I highly recommend.

As a Gen X-er you grow up not knowing so many of these things, and filling the knowledge gap is an incredible guilt trip that must leave the Catholic Church slacked-jawed in admiration. It’s a perfect storm for an entire generation of men and people-who-passed-as-men-back-then. They have a huge amount of frankly essential information missing, and the Orthrus and Cerberus guarding that knowledge are the handed-down shame that comes from discussing subjects you are programmed to see as taboo, and not even knowing exactly what it is that you don’t know so that you can look it up on the Internet later. Not excuses, of course, there are no valid excuses; just reasons.

Image by Piotr Zakrzewski from Pixabay

Ever wondered if there was a way to get my scintillating #content without having to do anything? Well oh my gosh, wonder no more!